-

Publication2014.3

-

Revisiting the “Place of Encounter with the Roots of Expression”

Norio Imai

(Artist)

This text was contributed to Borderless Art Museum NO-MA: Ten Years of History (2014).

Twenty years ago, when I was offered a position at a new art university, I was struck by the delight expressed by a friend who had been a university faculty member for a long time, who said, “How very lucky you are to be able to witness the opening of a new university!” Without much experience as a teacher, I did not appreciate how fortunate I was, but now, on the occasion of NO-MA’s tenth anniversary, I am deeply moved by the fact that I was lucky enough to be a part of these two new beginnings in Shiga Prefecture.

Be that as it may, ten years make a lot of difference, and during the ten years from 2004, when NO-MA opened, to today, social awareness and understanding of the expression of people with disabilities has indeed undergone significant changes. It would not be an overstatement to say that NO-MA has been at the center of pioneering and promoting these changes.

Another change is that the term “outsider art,” initially used as shorthand for such artistic expression, was replaced by “art brut” during this period. Both of these terms are not limited to the artistic expression of people with disabilities, but can also include expression by amateur artists who have not received specialized education in art and are not part of the established cultural system of the art world or art circles, and even the plastic arts of young children. In light of this, the term “art brut” will be used in this article, as its meaning of “raw and pure art” seems to better represent the purpose of NO-MA’s “borderless” policy.

It was two years before the opening of NO-MA that I rediscovered so-called art brut, when students from the art college where I worked decided to participate in a project of the Shiga Social Welfare Corporation as art supporters for disabled people, and I acted as a go-between.

The experience of being art supporters at a welfare facility was an encounter with the unknown for the art students. Many of them were deeply impressed by the unbounded expression of the people they supported, which in turn inspired their own creative endeavors and served as an opportunity to revisit the roots of their own expression. Some of them continued to work in this field after graduation.

This was how I became involved in the establishment of the Preparatory Committee, which was tentatively called the Shiga Prefecture Art Gallery for the Disabled, and since then I have been helping the project to the best of my limited ability, from the organization of the Steering Committee to the current meeting, and once as an exhibitor of a special exhibition.

We first needed to decide what kind of concept the facility should have.

Although it originally started as a gallery to display the works of people with disabilities, if the exhibitions were limited to such works, it might end up isolating them—the opposite of what we wanted. In terms of “unrestricted expression,” the artistic expression of disabled people is no different from the cutting-edge works of contemporary art unbound by common sense or social conventions. The facility was named Borderless Art Gallery NO-MA (later renamed Borderless Art Museum NO-MA) to reflect the idea of creating a place for open art and communication that would allow people to discover different roots of expression in the same field.

For the tangible aspects of the project, we held a number of discussions until we came up with the idea to renovate a townhouse from the Taisho era, but the location was still undecided at the beginning of the project. The renovation of old townhouses and modern buildings has long been called for by critics of the hectic “scrap and build” culture of Japan. However, I preferred the gallery not to be located on a floor of a multi-story building anyway, as I had been unable to forget my encounter with abstract paintings at the Gutai Pinacotheca, a small museum in Nakanoshima, Osaka, which used to be a storehouse in the Meiji era. As a result, it turned out to be a good decision to turn an old house in the Omi Hachiman Preservation District for Groups of Traditional Buildings into a unique, barrier-free small art museum. The planning stage, which focused on making the most of the spatial characteristics of the historic townhouse, was exciting not only for the members of the Social Welfare Corporation but also for us, the preparatory committee members.

Thus was born a base for steady and continuous activities, including exhibitions and symposia of paintings and sculptures created at welfare facilities in the prefecture, mainly through collaboration between people with disabilities and leading contemporary artists. The small pre-event held at the same location before the renovation is worth specific mention. It was an experimental exhibition that attempted to combine the works of two light and sound artists (Takashi Sasaoka and Yukio Fujimoto) with pictures and objects created by people with disabilities. This event actually marked the beginning of NO-MA.

Since its opening, this first unique activity center has become a hot topic of conversation, attracting welfare workers and art professionals from all over Japan. I have also continued the exhibitions at NO-MA and organize walks around Omi Hachiman as an off-campus activity for new students every year.

In 2006, the director of the Collection de l’Art Brut, a museum in Lausanne, Switzerland that houses and exhibits art brut plastic arts—formerly excluded from the realm of art history— came to Japan to conduct research on Japanese art brut, and gave a public lecture at the Seian University of Art and Design during her stay. As a result of the above research, an exhibition tour was held at NO-MA, Asahikawa, and Tokyo, and exhibitions were also held in Lausanne and Paris.

And so the wind of art brut blew. It is not easy to turn a gust of wind into a stable atmosphere, but these events certainly created the groundwork for art brut to take root and be recognized as an art and culture that is an essential part of human life. However, while I was deeply moved by the fact that this movement was being covered by various media as if it was a trendy phenomenon, I was also a little puzzled.

That is because, while I am pleased to see the greater social interest in and improved understanding of art brut, I believe that there has not yet been enough sober discussion on expression regardless of disabilities in relation to more conventional art forms. The excitement about art brut should not be limited to how interesting these works are.

In art brut, the origin of artists and the background of their disabilities often draw more attention than their works, but the works themselves should be discussed more in the context of art in general, without being bound by the word “disability.” In order to understand art brut in depth, it is important to interpret and enjoy the messages that art itself communicates, by being exposed not only to art brut but also to a wide range of contemporary art. Art is essentially the product of individual expression, whether the creator is abled or disabled.

Shiga Prefecture is undoubtedly a leading prefecture in welfare as well as environmental protection. In particular, it was not long after the end of World War II that facilities such as Omi Gakuen, where Kazuo Itoga and others laid the foundation for this work, began to engage in plastic arts activities for people with disabilities. Moreover, it has been a long time since the artistic development of clay sculpture in this area became prominent, including the involvement of Kazuo Yagi, a ceramic artist known for his objets d’art. I would like to celebrate the tenth anniversary of NO-MA, which was created to develop the tradition of practicing welfare and art, by looking back on those initial intentions.

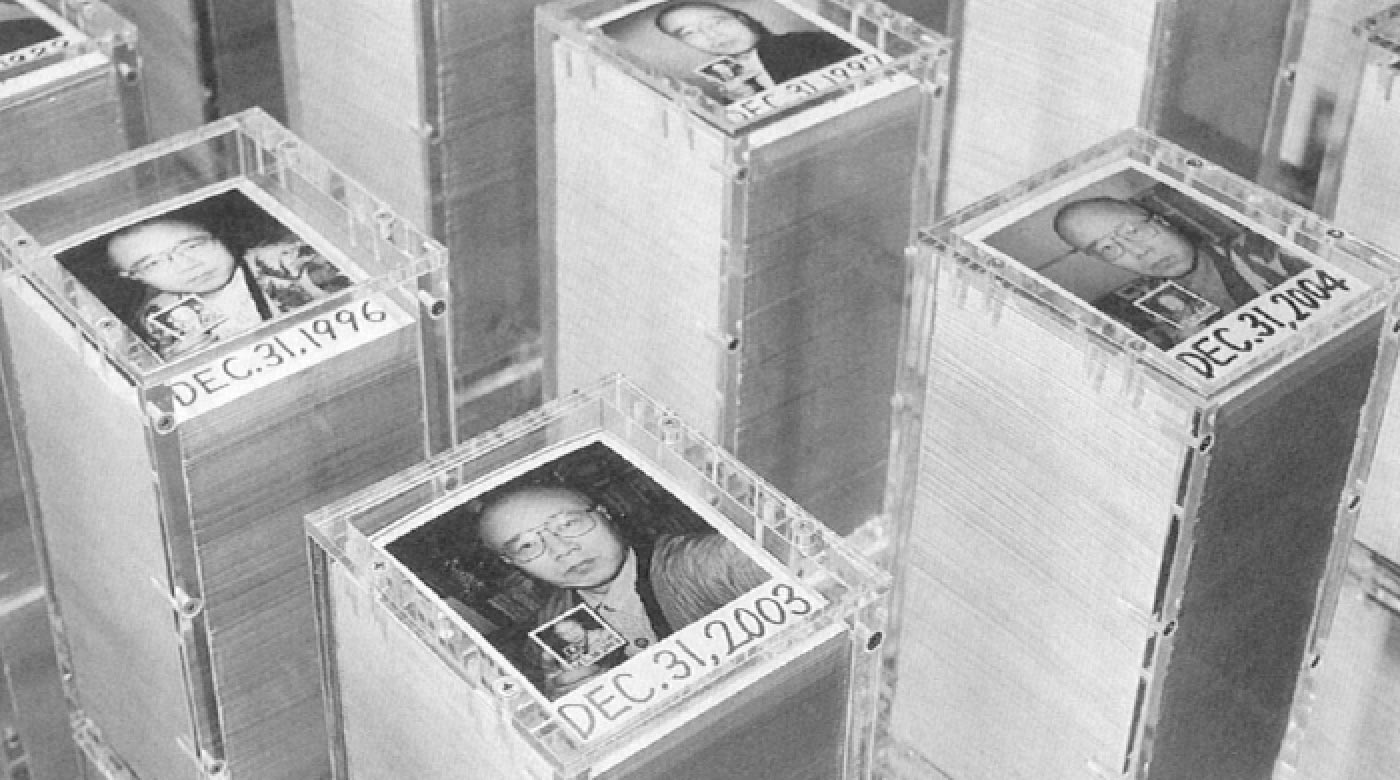

Daily Portraits (self-portraits since 1979) exhibited in My Rules: The Accumulation of My Time

Source: Borderless Art Museum NO-MA: Ten Years of NO-MA (published on March 31, 2014)

Project funded by Art Brut Promotion Projects in FY2013

Norio Imai

Born in Osaka in 1946. A former member of the Gutai group. He won the first prize of the 10th Shell Art Award in 1966. Since then, he has participated in many exhibitions both in Japan and abroad. He has also created monuments in front of Shin-Osaka Station, Keihan Tenmabashi Station, and along the street of Otsu City Hall, and received the Osaka City Urban Environment Amenity Award. He is the author of White to Begin: My Artbook (Brain Center) and the recently published Amateur Aesthetics: Takanabedaishi, the World of Yasukichi. He had a solo exhibition in Antwerp last year and in New York this spring.

(The profile of the author is extracted from the original text and refers to the time of writing.)